TPM 24: To hub-and-spoke, or not to hub-and-spoke? That is the question

The question of rates and annual contracts – and the effects of the Red Sea ...

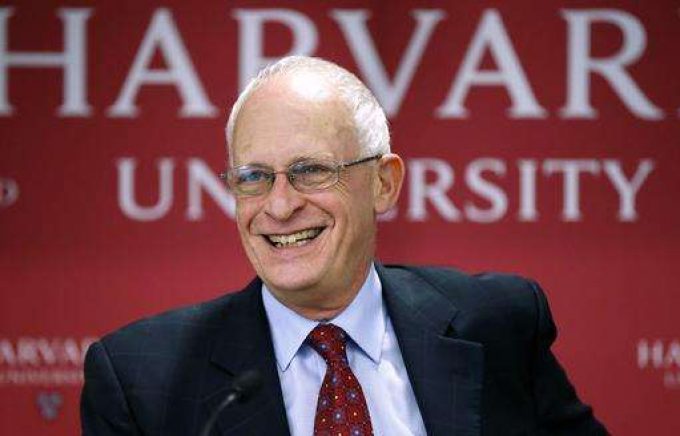

The 2016 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences was jointly awarded to Oliver Hart (pictured above) and Bengt Holmström for their contribution to ‘contract theory’, a subject that studies how economic actors enter contractual arrangements. The former is recognised for his work on researching the use of bargaining power in case of an asymmetric information. The latter is a specialist on the topic of incentives to guide behaviour.

Nobel Prize winners and the air cargo industry might seem as distant as Stockholm is to Shanghai. However, these theories explain some key dynamics in the air cargo industry.

In the case of asymmetric information, one contracting party has more – or better – information than the other, which puts it in a stronger bargaining position and therefore allows it to win a disproportionate share of the potential profits. Sounds familiar?

Ever since joining the air cargo industry, I have witnessed forwarders taking a larger share of potential profits than airlines. At the beginning of my career I was told that you can differentiate a forwarder employee from their airline counterpart by the size of their car. It seems to hold true to this day.

The individual forwarder has far better insight into the market dynamics (of shippers and airlines) than an individual airline. When these two parties sit at the negotiating table, the former will use this asymmetric information advantage to get the best possible deal. One could even argue that the sole perception of the airline – that the forwarder knows more than they do – is enough to create this imbalance in negotiation power.

And, although airlines are likely to play catch-up in this respect, some are creating different asymmetric information for themselves. It is about knowing more about how the forwarder has lived up to his commitment towards the airline than the forwarder knows himself. By creating this different type of asymmetric information, the airline creates a stronger negotiation power.

Here’s a very recent example: as part of its negotiations for the winter season, one forwarder wanted to have the price lowered while committing to the same weekly volumes. Having analysed the forwarder’s recent performance, however, the airline found a piece of information of which the forwarder was seemingly unaware. The airline discovered that the forwarder had not lived up to earlier committed volumes and was not sufficiently using the capacity reserved for it.

So, instead of conceding to the forwarder’s perceived position of power, the airline came up with an alternative proposal. It offered to reserve less space for the winter season (as the forwarder apparently needed less) and at the same price as the summer season. As that was not what the forwarder was looking for – it wanted more reserved capacity to deal with peak demand – it finally committed to the same conditions as the summer season.

“In life and in business you don’t get what you deserve, you get what you negotiate” is the title of a book by Chester Karrass, another expert on negotiating. Having asymmetric information in your back pocket will help you tip the balance in to your favour.

Niall van de Wouw is managing director of CLIVE. He can be reached at [email protected]

Comment on this article